The Often Overlooked Biodiversity

Benefits of Trophy Hunting

The Take home Message

- Arguments about the conservation value of trophy hunting almost exclusively revolve around the species being hunted, and tend to rely heavily on anecdotes and emotion.

- Scientific evidence that trophy hunting is a net positive or net negative for the species hunted is fairly weak, and not particularly convincing. The strong inferential evidence that scientists like to see in the best science certainly isn't available.

- A much more likely benefit of trophy hunting in places like Africa is that it serves as the impetus for private landowners to maintain large swaths of land in a semi-natural or natural state, thereby providing habitat for potentially thousands of species of insects, plants, small mammals, birds, and reptiles.

The full story

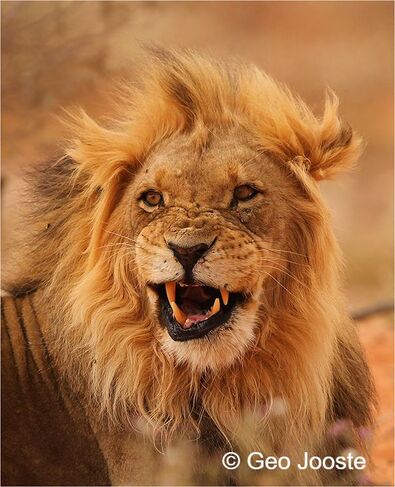

I'm not particularly convinced that trophy hunting either helps or hurts populations of trophy species like lions.

I'm not particularly convinced that trophy hunting either helps or hurts populations of trophy species like lions.

The role of trophy hunting in conservation has become perhaps the most controversial topic in conservation and environmental circles in the last few years. Clearly, trophy hunting has been a hot topic for decades, but social media seems to have intensified bickering over the practice. Everyone has an opinion, and as with most “conversations” that happen online, it seems the camps have become increasingly polarized over time. Nuance seems to escape those on both sides of the argument.

It’s fair to say that I have strong opinions about trophy hunting. I’m an obsessive hunter and a PhD-level ecologist and conservation biologist. I lived and conducted research in South Africa for more than two years and married a South African biologist who did research on leopards and gemsbok (an antelope popular among hunters). Given the aim of this website, I clearly think way too much about the intersection of hunting and conservation. What might surprise you is that my personal opinion and professional worldview on trophy hunting differ, and probably not in the way you would predict.

As a hunter, I despise the idea of trophy hunting. Killing an animal for the purposes of hanging it on the wall for bragging rights is unfathomable to me. You won't find any taxidermy in our house and I am very judicious about the pictures of harvested animals I post online. I find treating a harvested animal as a trophy to be unsavory. Americans and Europeans trophy hunting in Africa or Southeast Asia bothers me even more. The idea of traveling to another country to harvest their natural resources for bragging rights is a practice couched squarely in a long colonial history of exploitation. I find it morally questionable on many levels.

Conversely, in my professional capacity as an ecologist and conservation biologist, I recognize that trophy hunting can lead to positive conservation outcomes in some instances. This means I'm often forced to reconcile this scientific worldview with my personal feelings on trophy hunting. Understanding why I support trophy hunting for its conservation benefits might help explain how I do this. I doubt my worldview will sway any hardliners on either side of the argument, but what follows is my reasoning for professionally supporting a practice I personally despise.

First, I argue elsewhere the benefit of trophy hunting for conservation in the United States is negligible. Trophy hunting does occur in the US, but the conservation benefits of hunting here are largely driven by sport or recreational hunting, not trophy hunting (and yes, those are different things). This also misses the point of most online arguments about trophy hunting, which almost universally revolve around hunting large, charismatic game in African countries. That's what I'll focus on here as well.

The arguments you commonly see supporting trophy hunting are not the reason I support trophy hunting in Africa. I find those arguments to be tenuous and ineffective. The most common argument is a rehash of something called the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation, although that terminology is rarely used in this context. The short version as it relates to trophy hunting is that hunters pay for the privilege to pursue and harvest an animal. That money finds its way back into conservation and local communities, thereby leading to positive conservation outcomes for the species being hunted. The idea is that loss of a few individuals to hunting benefits the species as a whole. Shoot one black rhino to save the rest. The advocates of this argument, and there are many, will go to great lengths to prop up the idea that trophy hunting raises huge amounts of money while downplaying any negative aspects of removing animals from the population.

This and other common arguments are unconvincing to me because they lack strong inferential evidence that trophy hunting in places like Africa is a actually a net positive for commonly hunted species. The positives must outweigh the negatives, and that is really difficult to demonstrate. In fact, most of these arguments, even in the scientific literature, boil down to observations or anecdotes. Documenting the dollars trophy hunters spend or even that some of those dollars do make it to conservation agencies is a far cry from demonstrating a net positive benefit of trophy hunting on the species being hunted. Retelling the story of large declines in wildlife in Kenya after they implemented a hunting ban amounts to an anecdote with a sample size of one, even if it is a well documented anecdote. So at the risk of angering some colleagues, I have to say that I find the scientific literature about the effects of trophy hunting on the hunted species to be pretty weak.

Much of this has to do with my rather nerdy scientific opinion about how we best acquire "good" knowledge. I teach a class about how we acquire knowledge and what types of studies render the strongest evidence. Really strong evidence about the net effect of trophy hunting, either positive or negative, is pretty rare. Importantly, I'm not sure it's possible to ever conduct scientific studies about the effects of trophy hunting on the species being hunted that would rise to the level of inferential power we see in the best published science on other topics. Part of this can be chalked up to practical limitations. These are really hard questions to address because it’s next to impossible to set up a controlled study on trophy hunting when the intensity of hunting pressure is determined by governments. There will always be political and societal considerations that don't allow for the study a scientist would design in a perfect world. Even though we are often forced to make management decisions based on the best available science, we have to remember that the best available science is not necessarily good science. Frankly, that's where I think we're at in our understanding of the effects of trophy hunting on the hunted species. The best available science suggests trophy hunting is probably a slight positive for the hunted species, but that's a very tenuous conclusion.

It’s fair to say that I have strong opinions about trophy hunting. I’m an obsessive hunter and a PhD-level ecologist and conservation biologist. I lived and conducted research in South Africa for more than two years and married a South African biologist who did research on leopards and gemsbok (an antelope popular among hunters). Given the aim of this website, I clearly think way too much about the intersection of hunting and conservation. What might surprise you is that my personal opinion and professional worldview on trophy hunting differ, and probably not in the way you would predict.

As a hunter, I despise the idea of trophy hunting. Killing an animal for the purposes of hanging it on the wall for bragging rights is unfathomable to me. You won't find any taxidermy in our house and I am very judicious about the pictures of harvested animals I post online. I find treating a harvested animal as a trophy to be unsavory. Americans and Europeans trophy hunting in Africa or Southeast Asia bothers me even more. The idea of traveling to another country to harvest their natural resources for bragging rights is a practice couched squarely in a long colonial history of exploitation. I find it morally questionable on many levels.

Conversely, in my professional capacity as an ecologist and conservation biologist, I recognize that trophy hunting can lead to positive conservation outcomes in some instances. This means I'm often forced to reconcile this scientific worldview with my personal feelings on trophy hunting. Understanding why I support trophy hunting for its conservation benefits might help explain how I do this. I doubt my worldview will sway any hardliners on either side of the argument, but what follows is my reasoning for professionally supporting a practice I personally despise.

First, I argue elsewhere the benefit of trophy hunting for conservation in the United States is negligible. Trophy hunting does occur in the US, but the conservation benefits of hunting here are largely driven by sport or recreational hunting, not trophy hunting (and yes, those are different things). This also misses the point of most online arguments about trophy hunting, which almost universally revolve around hunting large, charismatic game in African countries. That's what I'll focus on here as well.

The arguments you commonly see supporting trophy hunting are not the reason I support trophy hunting in Africa. I find those arguments to be tenuous and ineffective. The most common argument is a rehash of something called the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation, although that terminology is rarely used in this context. The short version as it relates to trophy hunting is that hunters pay for the privilege to pursue and harvest an animal. That money finds its way back into conservation and local communities, thereby leading to positive conservation outcomes for the species being hunted. The idea is that loss of a few individuals to hunting benefits the species as a whole. Shoot one black rhino to save the rest. The advocates of this argument, and there are many, will go to great lengths to prop up the idea that trophy hunting raises huge amounts of money while downplaying any negative aspects of removing animals from the population.

This and other common arguments are unconvincing to me because they lack strong inferential evidence that trophy hunting in places like Africa is a actually a net positive for commonly hunted species. The positives must outweigh the negatives, and that is really difficult to demonstrate. In fact, most of these arguments, even in the scientific literature, boil down to observations or anecdotes. Documenting the dollars trophy hunters spend or even that some of those dollars do make it to conservation agencies is a far cry from demonstrating a net positive benefit of trophy hunting on the species being hunted. Retelling the story of large declines in wildlife in Kenya after they implemented a hunting ban amounts to an anecdote with a sample size of one, even if it is a well documented anecdote. So at the risk of angering some colleagues, I have to say that I find the scientific literature about the effects of trophy hunting on the hunted species to be pretty weak.

Much of this has to do with my rather nerdy scientific opinion about how we best acquire "good" knowledge. I teach a class about how we acquire knowledge and what types of studies render the strongest evidence. Really strong evidence about the net effect of trophy hunting, either positive or negative, is pretty rare. Importantly, I'm not sure it's possible to ever conduct scientific studies about the effects of trophy hunting on the species being hunted that would rise to the level of inferential power we see in the best published science on other topics. Part of this can be chalked up to practical limitations. These are really hard questions to address because it’s next to impossible to set up a controlled study on trophy hunting when the intensity of hunting pressure is determined by governments. There will always be political and societal considerations that don't allow for the study a scientist would design in a perfect world. Even though we are often forced to make management decisions based on the best available science, we have to remember that the best available science is not necessarily good science. Frankly, that's where I think we're at in our understanding of the effects of trophy hunting on the hunted species. The best available science suggests trophy hunting is probably a slight positive for the hunted species, but that's a very tenuous conclusion.

Instead, the reason I support trophy hunting for conservation is that it provides financial incentives for private landowners to maintain large swaths of land in a natural or semi-natural state. Game farms with hunting concessions exist because of trophy hunting, but their most tangible conservation function is that they provide habitat for thousands or tens of thousands of native plant and animal species that might otherwise receive little protection.

These secondary benefits of trophy hunting for non-game species are both far more likely to be true and have much higher potential to be documented in a scientifically sound manner than arguments that trophy hunting benefits the hunted species. There are a few reasons for this, but simplest comes down to the feasibility of conducting experiments on the topic. I can think of dozens of high quality projects to address questions about the biodiversity value of land protected for trophy hunting. This is key to me as a scientist. I can foresee a time when we have strong evidence trophy hunting is beneficial for biodiversity. I find it hard to imagine the same will ever be true about evidence trophy hunting benefits the hunted species.

Game farms are likely to be especially important for conserving biodiversity in places where public land is limited. For example, my wife grew up in a sparsely populated province called the Free State, which can best be described to an American as the Kansas of South Africa. In the Free State, and the neighboring Northern Cape, the few national parks are located in environmentally unique areas like the Kalahari Desert or the Namaqualand. Outside national parks and a few smaller provincial parks, the remaining natural habitats are found mostly on private ranches used for either ecotourism or trophy hunting. Otherwise, you’ll find vast expanses of land dedicated to row crops and livestock grazing. The conservation relevance of game farms in this region is not that they provide habitat for lions, eland, and gemsbok, but instead that they provide habitat for elephant shrews, sunbirds, dung beetles, snakes, and native plants.

Now imagine the ramifications for biodiversity in places like the Free State if trophy hunting becomes illegal. A common refrain among those opposed to trophy hunting is that game ranches could replace hunting with non-consumptive forms of recreation, like ecotourism and photo safaris. This sounds great, and I wish it were true, but it ignores some very real practical limitations. For example, many game ranches are only equipped to maintain species like antelope, not the large megafauna most ecotourists from the US or Europe want to see. The fences necessary to keep lions, rhinos, and elephants would alone require investments well into the millions of dollars for a large game ranch.

Even assuming a game ranch could afford the capital investment necessary for upgrades, it's not clear such a switch would be profitable. The ecotourism industry in southern African countries is well established, and there isn’t an obvious need for a glut of new ranches dedicated to ecotourism. Until someone can demonstrate where all the new tourists would come from to keep newly converted ranches in business, the ecotourism model is not financially viable for most of them. Unfortunately, for many hunting concessions, the financial alternative to trophy hunting probably isn’t ecotourism, it’s farming or ranching or mining.

Most game farms aren't constructed to maintain the "big five" species like elephants, rhinos, and lions. Instead, fences like this are common, which are more than adequate for common game species like antelope, giraffes, and some more dangerous species like Cape buffalo. This particular ranch is a breeding ranch that sells game to other farms, including hunting concessions.

Thus, the loss of trophy hunting would mean the land use on many ranches would change dramatically. While this would certainly lower the overall number of lions or eland, it likely wouldn’t lead to the extinction of these species because they are also found in public parks and on private ecotourism ranches across southern and eastern Africa. Most game species are large, with wide geographical ranges, so they can be protected in many parks across many countries. Apart from a few rare antelope species and heavily poached species like rhinos, populations of large animals on hunting ranches are usually peripheral to the broader conservation efforts for those species.

Conversely, many plants and small animals have highly localized ranges. The beetle or lizard you find on one game farm is likely to be a different species than you would find on a national park 50 or 100 or 200 miles away. Private lands can serve as the strongholds for species with smaller ranges. The conversion of hunting ranches to agriculture or ranching would undoubtedly lead to the extinction of some of these species, many of which scientists probably haven’t even had a chance to name yet.

And that alone is the reason I professionally support some trophy hunting in southern and eastern Africa even though I personally despise the practice. I recognize that my interest in the viability of localized plant and animal populations is far from universal. I’m an ecologist and conservation biologist; it is literally my job to care about such things. The diversity of plants and small animals just isn’t something most people think about when you mention conservation, but from a biodiversity standpoint, those species are vital. There a perhaps a few hundred large, charismatic species most people think of when you mention wildlife. There are thousands of species of small mammals, birds, reptiles, and fish that are unfamiliar to most people, as well as millions of species of insects and plants. This is where we will lose most of the biodiversity over the next century.

I'm not sure why you don't see this argument regularly outside scientific circles. Sure, it pops up here and there, but it's an argument that conservation biologists need to be making over and over again to the public. Getting into shouting matches with animal rights activists about whether killing Cecil the Lion was a positive or negative thing for lions in general is a pointless endeavor. It will only serve to strengthen the resolve of those who don't want to recognize the conservation benefits of trophy hunting. The biodiversity benefits of trophy hunting can be documented and might actually change a few minds of people on the fence about trophy hunting. It seems like a much more valuable use of time and research money to me.