The (Land)Owners of Conservation

Tallying the Land Protected in The United States

|

Part I

|

The Take home Message

- Protecting land from destruction is the backbone of the American conservation system.

- Conservation land in the United States is owned by private citizens, non-governmental organizations, and local, state, tribal, and federal governments, representing a wide range of land-use priorities.

- State and federal governments are by far the largest landowners. State land, more likely to be ultimately paid for by hunters and anglers, is more important in the eastern United States. Federal land, either claimed long ago or paid for by normal budgetary operations, is more prominent in the western United States.

The full story

Hunters spend hundreds of millions of dollars each year on licenses and permits and hundreds of millions of dollars on taxes associated with purchasing guns, ammo, and archery equipment. Through these mechanisms, hunters provide about $1.5 billion for game management and conservation each year, money that is mostly used to fund state fish and game agencies around the country. In many states, these funds literally keep fish and game agencies in business, and are often used as evidence of the importance of hunters in the functioning of the conservation complex in the United States.

Critically evaluating the relationship between hunting and conservation is really at the heart of this website. If we look past the sound bites that pop up in every story about hunting and conservation, can we get a better grasp of the role hunters really play in conservation? Each story I write here addresses a different aspect of this question. Here, I'll focus on the acquisition and management of public lands. Hunters, hunting-interest groups, and state agencies are quick to tout land purchases made with money from hunting licenses and taxes on hunting equipment not only for the recreational opportunities they will afford sportspeople, but also for the more general conservation benefits they might provide. In theory, these conservation benefits are shared by all residents. Unfortunately, the argument that sportspeople are vital for protecting natural lands is almost always made without context. It makes sense for hunters and state agencies to lean heavily into the conservation benefits of state lands purchased with hunter-derived dollars because doing so serves an explicit purpose: it is a valuable public relations tool to sell the benefits of hunting to a sometimes skeptical public.

As an ecologist and a hunter, I've been lucky enough to spend extensive time exploring protected lands around the United States. I've seen some the best protected lands in the country, as well as some properties where conservation clearly isn't working. The intersection of my work and hobby has led me to question why such variation exists, and more specifically how land protected indirectly by sportspeople stacks up against land protected through other means.

I'll preface what follows by pointing out that any attempt to answer such a question will be necessarily superficial. One could write an entire book on just this one topic. Still, it's at least possible to begin such a conversation with some crude stats about land ownership in the United States and some qualitative (and very general) assessments of the conservation impacts of land owned by various stakeholders and agencies. Here, I’ll focus on the quantity of lands protected for conservation purposes, which is where hunters and state agencies tend to focus their attention. In Part II, I’ll discuss the quality of lands protected.

Critically evaluating the relationship between hunting and conservation is really at the heart of this website. If we look past the sound bites that pop up in every story about hunting and conservation, can we get a better grasp of the role hunters really play in conservation? Each story I write here addresses a different aspect of this question. Here, I'll focus on the acquisition and management of public lands. Hunters, hunting-interest groups, and state agencies are quick to tout land purchases made with money from hunting licenses and taxes on hunting equipment not only for the recreational opportunities they will afford sportspeople, but also for the more general conservation benefits they might provide. In theory, these conservation benefits are shared by all residents. Unfortunately, the argument that sportspeople are vital for protecting natural lands is almost always made without context. It makes sense for hunters and state agencies to lean heavily into the conservation benefits of state lands purchased with hunter-derived dollars because doing so serves an explicit purpose: it is a valuable public relations tool to sell the benefits of hunting to a sometimes skeptical public.

As an ecologist and a hunter, I've been lucky enough to spend extensive time exploring protected lands around the United States. I've seen some the best protected lands in the country, as well as some properties where conservation clearly isn't working. The intersection of my work and hobby has led me to question why such variation exists, and more specifically how land protected indirectly by sportspeople stacks up against land protected through other means.

I'll preface what follows by pointing out that any attempt to answer such a question will be necessarily superficial. One could write an entire book on just this one topic. Still, it's at least possible to begin such a conversation with some crude stats about land ownership in the United States and some qualitative (and very general) assessments of the conservation impacts of land owned by various stakeholders and agencies. Here, I’ll focus on the quantity of lands protected for conservation purposes, which is where hunters and state agencies tend to focus their attention. In Part II, I’ll discuss the quality of lands protected.

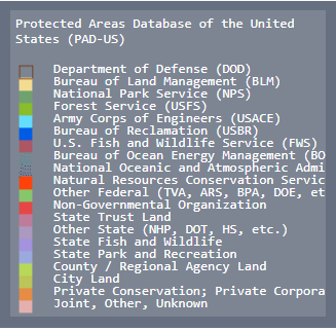

The protected lands in the United States are heavily concentrated in the western United States and Alaska with the majority of public land held by the federal government. In the eastern United States, local and state governments are often more important players in protecting conservation lands. These maps are from the USGS Protected Areas Database (https://maps.usgs.gov/padus/).

I was lucky enough to explore some of the extensive county forests in Wisconsin during a recent ruffed grouse hunt.

I was lucky enough to explore some of the extensive county forests in Wisconsin during a recent ruffed grouse hunt.

There are six classes of land ownership most relevant to conservation in the United States: 1) private, 2) non-governmental organizations, 3) tribal government or indigenous leadership, 4) local government (either municipality or county), 5) state government, and 6) federal government. In the broadest sense, each entity tends to own or purchase land with different characteristics. Some entities own large swaths of land, others focus on protecting smaller, but ecologically or environmentally important areas. Many people mistakenly assume conservation only happens on government-owned properties, but government control isn’t always the best conservation solution.

Private Lands

Private landowners can play vital roles in conservation and could represent one of the most important pathways for protecting biodiversity in the future. A pollinator garden in a yard can increase local insect biodiversity and a rooftop garden can act as an important stopover point for migrating insects and birds. You do not need to own acres of land to have a positive effect on biodiversity. However, landowners with large tracts have the greatest opportunity to be impactful conservationists, even if that opportunity is often unrealized. There are some private landowners that own almost unbelievably large amounts of land, and several of the private landowners with the largest holdings in the United States also have stated conservation goals. Ted Turner, of CNN fame, owns about 2 million acres, and has a reputation for a strong conservation ethic. Don’t get me wrong, Ted Turner is definitely a capitalist who believes humans should use the environment, but he is better than some about recognizing the importance of human-nature coexistence. In many cases, landowners hoping for positive conservation outcomes on their property can leverage state or federal funding from the Farm Bill and other sources to maximize their conservation impact. In others, they take advantage of tax incentives by placing their property in land trusts.

For all the potential benefits of conservation on private lands, there are two main difficulties that can make private conservation unreliable. First, it is often impossible to verify the value of conservation efforts for biodiversity and ecosystem functioning on private lands. Second, much (if not most) conservation on private lands is transient. There are federal programs, like the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP), that incentivize conservation on private lands over years or decades, but even that might not be long enough to reverse years of damage done to an ecosystem by human use. Further, conservation-minded landowners are still rare enough that whatever conservation efforts are put in place by a landowner can be undone when the property is sold. Neither of these are reasons to avoid conservation efforts on your own land, but they must be considerations of the conservation community when crafting large-scale conservation measures.

Non-governmental Organizations (NGOs)

Few non-governmental organizations own large swaths of protected land, but many have been successful at using other means, like land trusts, to protect substantial areas of land. The Nature Conservancy sticks out as one of the most important in terms of overall land protection, with tens of millions of acres protected in North America. Most conservation NGOs can’t compete with The Nature Conservancy in acreage of land protected, so they are often more interested in protecting or conserving a specific habitat or group of animals and focus their efforts on important sites for meeting those goals. For example, I often work with an NGO called Bat Conservation International who focuses their land acquisition priorities on important caves for bat colonies. Similarly, the better known and larger Audubon Society owns some of the most important bird habitats in North America.

Indigenous and Tribal Lands

There is a quickly growing recognition of the importance and value of indigenous protected lands. Tribal and indigenous lands often hold some of the most valuable ecosystems in their most natural states, with most concentrated in western states and Alaska. In the United States, for example, indigenous groups own or manage 11% of the highest quality, intact forest landscapes. Some of the tribal lands on which I have worked were huge, covering tens of thousands of square miles. They also serve as an interesting conservation case. They were often “given” to Native American tribes because the US government viewed them as low value land for agriculture or forestry. Not coincidentally, the lands viewed as low value by most people until the 20th century are often highly valuable for conservation. The conservation done on these lands is quite often first rate, and even the federal government is beginning to recognize this through funding streams specifically aimed at conservation on tribal lands.

Non-governmental organizations often focus their efforts on purchasing small, but important habitats for protecting a specific plant, animal, or habitat. Bracken Cave, which was protected largely through the efforts of an NGO called Bat Conservation International, is home to hundreds of thousands of Mexican free-tailed bats.

Local Governments

Local governments most often own small swaths of land, either in small city parks or in areas aimed at protecting valuable resources like a reservoir and the surrounding land to provide drinking water. There are some notable exceptions like the 30,500-acre McDowell Sonoran Preserve owned by Scottsdale, Arizona and the 16,000-acre South Mountain Park owned by Phoenix. Large municipal parks with high conservation value are rarer in the eastern United States, but they do exist. Jefferson Memorial Forest is a high biodiversity, 6,500-acre eastern deciduous forest owned by Louisville, Kentucky. There are also some fairly large county forests in the northern Midwest. Some municipalities have also begun preparing for future growth by purchasing and protecting open spaces around the edge of the current sprawl with the goal of maintaining open spaces as the city grows. Rarely are these purchased specifically for wildlife and native plant conservation, but they might hold some value in that regard.

State Governments

In terms of acres owned explicitly for protection of natural resources, state and federal governments are clearly the two biggest players. State governments own approximately 200 million acres, with slightly over half of that in Alaska. State lands comprise about 5% of the land outside Alaska and range from 0.3% of the land in Nevada to 34.2% of the land in Hawai’i. Depending on the state, the properties relevant to conservation might be called fish and wildlife areas, wildlife management areas, conservation areas, state forests, state grasslands, or a host of others. State-owned lands are probably the hardest land-ownership category to generalize. They are most often intermediate in size, with relatively few areas outside Alaska exceeding 10,000 acres. State governments also vary widely in their land acquisition priorities. Some lands are purchased to protect specific habitats or valuable natural resources while others may be donated to states from conservation-minded landowners, in which case they can be a mixed bag of quality. State lands are those most likely to be purchased by hunting and fishing dollars, so when someone talks about hunters protecting land, these are generally the areas to which they refer.

Federal Government

The federal government is by far the largest landowner in the United States, and conservation-related lands can be found under the control of several agencies. By far the largest area is managed by the Bureau of Land Management, with nearly 250 million acres. Most BLM land is heavily used, and often abused, for ranching and mineral extraction. However, BLM lands do include a sizeable amount of wilderness and conservation land. The US Forest Service manages 193 million acres of multi-use properties. While generally not managed specifically for conservation, much of this land does contain forest or grasslands with considerable conservation value, including wilderness areas. The US Fish and Wildlife Service owns 89 million acres in National Wildlife Refuges and waterfowl production areas. A primary goal of nearly all USFWS properties is to conserve and protect natural habitats and wildlife. Some areas allow hunting, agriculture, or light grazing, but some of the most valuable preserved land in the United States can be found on USFWS properties. The USFWS is also the only federal agency that has uses hunter dollars (mostly collected from sales of Duck Stamps) to purchase sizeable amounts of land. The National Park Service manages 80 million acres of some of the most pristine and important ecosystems in the United States. The removal of resources and consumptive recreation is prohibited on NPS lands. Finally, and somewhat surprisingly, the Department of Defense has sizeable holdings of land with moderate to high conservation value. While conservation is clearly not the primary purpose for protection of these areas, their sheer size does make some DOD lands important for conservation.

Hunters and anglers contribute money, time, and effort to conservation on land in several of these ownership categories. Private landowners often protect parts of their property, even if it's just a fencerow left uncut, because they like to hunt. Sportspeople donate time and money to NGOs like Ducks Unlimited or Pheasants Forever, who protect substantial tracts of land. Money spent on Duck Stamps is used to increase the properties under federal protection. And most importantly, a sizeable portion of state protected areas have been purchased using Pittman-Robertson funds and hunting license and permit fees.

Determining how much land has been protected by private landowners is almost impossible (with the exception of CRP land, which I'll come back to shortly). It's also quite difficult to determine how much of the land protected by Ducks Unlimited or Pheasants Forever can be attributed to dollars originating from hunters because these organizations also get considerable funds from state and federal governments. Therefore, perhaps the most tangible demonstration of the relative importance of hunters and anglers in funding land acquisition is a comparison of the conservation lands held by state and federal governments throughout the United States. We can make the broad generalization that hunters are very important in paying for state-owned lands. Conversely, most federal protected lands were purchased through normal budgetary purposes or “claimed” (or more precisely, stolen) generations ago by the federal government.

To make this comparison, I tallied land used to protect natural resources by state and federal governments. To be conservative, I determined how much land under federal control is classified as a conservation area, national park, national monument, or wilderness area and is thus afforded a higher level of protection from resource extraction and grazing than most federal lands. This excluded, for example, national forests subject to logging (we’ll come back to this assumption) and BLM land subject to heavy grazing or mineral extraction, even those such areas might have some conservation value. For simplicity, I also ignored land owned by the Department of Defense and all other non-state and non-federal entities.

At the national level, approximately 55% of government-owned conservation land is controlled by the federal government and 45% is controlled by state governments (again, ignoring land owned by other entities). The national comparison gives only a crude picture of the relative importance of sportspeople's dollars in procuring conservation lands. It’s more interesting to look at land ownership at the state level, where strong regional trends become apparent. Most notably, there is a stark difference in conservation land ownership between western states and states east of the Rockies. The federal government is a much bigger player in conservation in western states, with Florida being the only state east of the Mississippi River where the federal government holds more than 10% of the area of the state in protected status.

Under my outlined assumptions, state governments protect more conservation land than the federal government in 37 states. Remember, however, that I excluded most forest service lands from this comparison, which may be overly conservative because at any given time, a substantial proportion of Forest Service land is composed of mature forest, which has high conservation value. If even 50% of Forest Service land is considered of high conservation value, state governments protects more conservation land than the federal government in 27 states. If we further consider CRP land, which is in effect a federal-private partnership, the number drops even lower. Even limiting the estimate to only high-quality CRP land, that land categorized under something called continuous enrollment, means only 20 states have more state-protected land than federally protected land. In fact, in six states, total CRP enrollment alone outstrips state-owned land.

States that fall above the diagonal line have more state protected land for conservation than federal protected land for conservation; states that fall below the line have more federal protected land. Great Plains and eastern states are in gray, western states are in black. There is little protected land in most eastern states, so they are clumped in the bottom left corner of the graph. I have ignored CRP land in this figure because it is technically owned by private citizens even though the protection mechanism is ultimately funded by the federal government.

While the amount of land protected by the federal government dwarfs the amount of state land, dollars provided by sportspeople have been particularly important in protecting land in the eastern half of the country and the upper Midwest. In some contexts then, hunters and anglers have much to brag about for the funding they have provided for the acquisition and management of lands aimed at protecting natural resources. Without hunting licenses and Pittman-Robertson excise taxes, some habitats, like eastern deciduous forests, would be even more vulnerable to habitat fragmentation and destruction than they already are. Still, while having the funds to purchase and protect a property is a necessary step for conservation in many places, that alone is not sufficient. How a property is managed is also vital to the effectiveness of a property in meeting conservation goals. So how do lands purchased with fees raised from hunting licenses and taxes from gun sales stack up in quality compared to other conservation lands? I detail my impressions in Part II.

While the amount of land protected by the federal government dwarfs the amount of state land, dollars provided by sportspeople have been particularly important in protecting land in the eastern half of the country and the upper Midwest. In some contexts then, hunters and anglers have much to brag about for the funding they have provided for the acquisition and management of lands aimed at protecting natural resources. Without hunting licenses and Pittman-Robertson excise taxes, some habitats, like eastern deciduous forests, would be even more vulnerable to habitat fragmentation and destruction than they already are. Still, while having the funds to purchase and protect a property is a necessary step for conservation in many places, that alone is not sufficient. How a property is managed is also vital to the effectiveness of a property in meeting conservation goals. So how do lands purchased with fees raised from hunting licenses and taxes from gun sales stack up in quality compared to other conservation lands? I detail my impressions in Part II.